Conran really did change our lives back in the seventies. Whereby your Mum would look down her nose at your ‘bare’ flat that, in her opinion, was missing the three-piece suite, the sideboard, patterned carpet and the array of naff lampshades that her generation saw as a sign of style and prosperity. Conran saw that as dreadful and spent his entire life making the country more cosmopolitain and contemporary - before we even knew what that word meant.

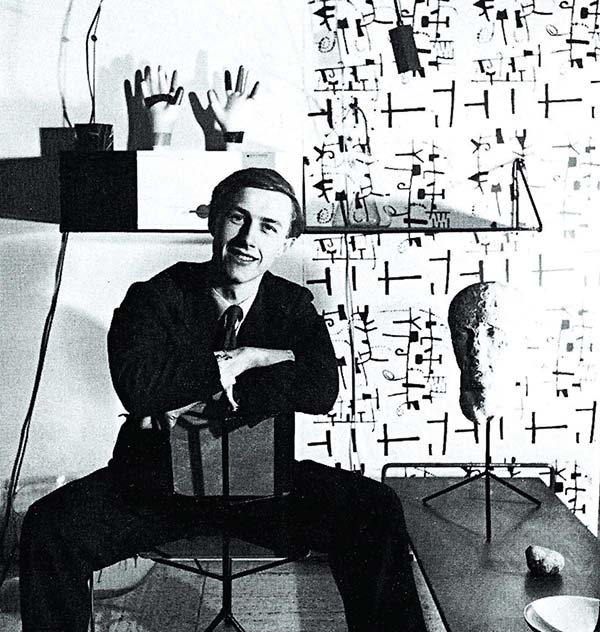

Born in 1931, Sir Terence studied textile design at London’s Central School of Art before he set up a workshop with his tutor, the artist and print-maker Eduardo Paolozzi. Here, he concentrated on furniture design, ceramics and fabrics.

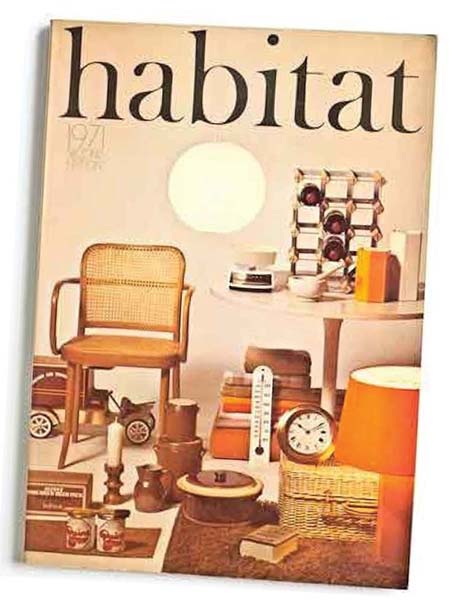

Then, in the early 1950s, he worked on the Festival of Britain alongside architect Dennis Lennon. However, Sir Terence really became a household name in the 1960s, as one of the key designers of that decade. In 1964, he founded Habitat, the furniture company that he grew from a single, high-profile outlet in London to become an international chain. Habitat was the springboard for Conran’s expansion into the retail mainstream. As the founder of the Storehouse Group, he acquired the Heal’s furniture business, set up Next and ran British Home Stores and Mothercare. He opened the first Conran Shop in 1972, with eight stores located in London, Paris, New York and across Japan.

Sir Terence was also at the forefront of professionalising design in Britain throughout his life. Founded over 60 years ago, The Conran Design Group demonstrated the best of design in Britain, specialising in interiors, hotel and restaurant design, graphics, products and homeware. He would also go on to establish an architectural practice with Fred Lloyd Roche called Conran Roche that eventually became Conran and Partners.

Alongside design, food was also one of Terence’s great passions and he became a renowned restaurateur. His first restaurant, with Ivan Storey, The Soup Kitchen, opened in London in 1953 and he went on to open many more including Pont de la Tour, Bibendum, Orrery, Quaglino’s and Mezzo.

In a statement, Sir Terence’s family wrote: “He was a visionary who enjoyed an extraordinary life and career that revolutionised the way we live in Britain. It gives us great comfort to know that many of you will mourn with us, but we ask that you celebrate Terence’s extraordinary legacy and contribution to the country he loved so dearly.”

“I’m a Bauhaus-educated chap,” he told Vanity Fair last year, before spelling out his philosophy of design, that objects should be “economic, plain, simple and useful”. On these points he was remarkably consistent: he would have said something very similar at any time in the past seven decades, ever since he was a student at what was then called the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, or even at the design-aware Bryanston School in Dorset.

He was, to be more precise, a product of that version of modernism that developed around the Festival of Britain of 1951, on which he had worked. As also expressed in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s influential Britain Can Make.

It exhibition of 1946, it was the idea that postwar Britain could, with the help of enlightened modern design, both enhance the quality of everyday life and rediscover its ability to make things.

His shops and restaurants really did change the visual and gastronomic culture of the country. It has often and accurately been pointed out that, along with the cookery writer Elizabeth David and the fashion designer Mary Quant, he helped to bring some continentally inspired joie de vivre to what was a drab place. “It is hard to overstate how uninteresting London was then,” he said of his early years in the city, “it really was the era of Spam fritters.”

Conran’s most cited achievements include the introduction or popularisation of such things as flat-pack furniture, paper lanterns, duvets, espresso machines and woks. Also the chicken brick, a once-popular terracotta device for cooking poultry. His many restaurants played a leading role in transforming Britain’s reputation as a gastronomic wasteland.

If none of these innovations were essential to existence, they could certainly add to the enjoyment of it – Conran’s claim that his promotion of duvets “undoubtedly changed the sex life of Europe” was only partly hyperbolic. Ultimately Conran’s work was about pleasure, about making a sort of tasteful hedonism widespread.

His personal life, with four marriages and many affairs, might also be said to have been about pleasure, although with sometimes spectacular divorces and widely reported family tensions that belied the calm of his design aesthetic.

If Conran’s core clientele was a certain kind of metropolitan buyer and diner, his influence can be seen in the products of Ikea, in restaurant menus all over the country, in the popularity of what now gets called “contemporary design”.

"Terence Conran has filled our lives for

generations with ideas, innovation and brilliant

design. He leaves a treasure trove of household and industrial design that will stay with us forever ❜❜

Lord Mandelson, Chairman of the board of trustees at the Design Museum

Conran the businessman did well in the era of Margaret Thatcher, including through canny property development, but he never accepted her politics. “She was one of the most odious people who’ve ever walked the earth,” he called her. She, for her part, was outraged that the Design Museum’s displays included objects made by foreigners. Conran found Tony Blair much more congenial, and the feeling was mutual, at least until Conran opposed the invasion of Iraq.

He was a prominent representative of Cool Britannia, of the young-at-heart and stylish country that New Labour wished to promote. The Blairs entertained the Clintons at Conran’s Pont de la Tour restaurant. When the French president Jacques Chirac visited for a summit, Conran designed the setting. “I’ve seen the fuchsia and it works”, wrote the Daily Telegraph columnist Boris Johnson.

“Oh, I have a lifetime of anecdotes after a very long career in design, furniture and retail,’ Conran once said. ‘An early one that sticks in my mind was in the mid-50s as a member of the Royal Society of Industrial Artists, which had strict rules that members should not compete with one another.

‘I desperately needed more work, so produced a simple newsletter to send to potential clients telling them what work we had done and suggesting how our services might benefit them. I received an irate phone call from the secretary of the society, as there had been complaints about our newsletter from other members. He suggested a club in Pall Mall if I wanted more work. I was appalled by this and continued to produce my letters, and I was thrown out of the society. Can you imagine a company today not being allowed to promote themselves commercially in the marketplace? They would be out of business before they even began.’

Looking back on his career in an interview with Furniture News, Sir Terence thrill of seeing all our hard work and enterprise a decade earlier coming to fruition, was very special’.

‘We’d overcome so much frustration at the established order who didn’t believe in any of the ideals and beliefs that we were so passionate about,’ he said. ‘By the early 60s we’d designed first-rate furniture for a modern generation, but the retailers just wouldn’t accept it or display it properly - so we opened our own shop instead.’

His career high point? ‘I suppose the high point would have been when we floated the business and we really knew we’d made it. Our little baby had grown up and there were stores not only all round Britain, but all over the world, too. We’d created a highly profitable, popular and successful global brand.’

Sir Terence began making furniture at the age of only 10. He recalled having a small room in Warwick Gardens in around 1947 which he ‘absolutely detested’ - so set up a small workshop. ‘That allowed me to do smaller pieces of work for other people, and it built from there. Establishing bigger premises, eventually employing staff, taking on machinery … before you know it, you’re running your own furniture business,’ he said. ‘Looking back, I’m rather proud of my early furniture and it seems relatively fresh today.’

He was married four times, including to Shirley Conran, who helped launch Conran Design before becoming the author of self-help books like Superwoman and the racy bestseller Lace.

Their sons Jasper and Sebastian Conran both became designers, while his other three children - Tom, Sophie and Ned - by his third wife, food writer Caroline, have forged successful careers in the creative sector, notably in food writing and as restaurateurs. He was knighted in 1983 for services to design.