In a time when the country has rarely felt so divided and split, it took the unlikely figure of Danny Dyer (the Albert Square landlord not the Love Island victor) to say something about Brexit that almost EVERYONE agreed with.

“Where is the geezer?” he demanded on Good Evening Britain, along with a few choice insults. “How comes he can scuttle off? He called all this on. Where is he? He’s in Europe, in Nice, with his trotters up, yeah, where is the geezer? I think he should be held to account for it.”

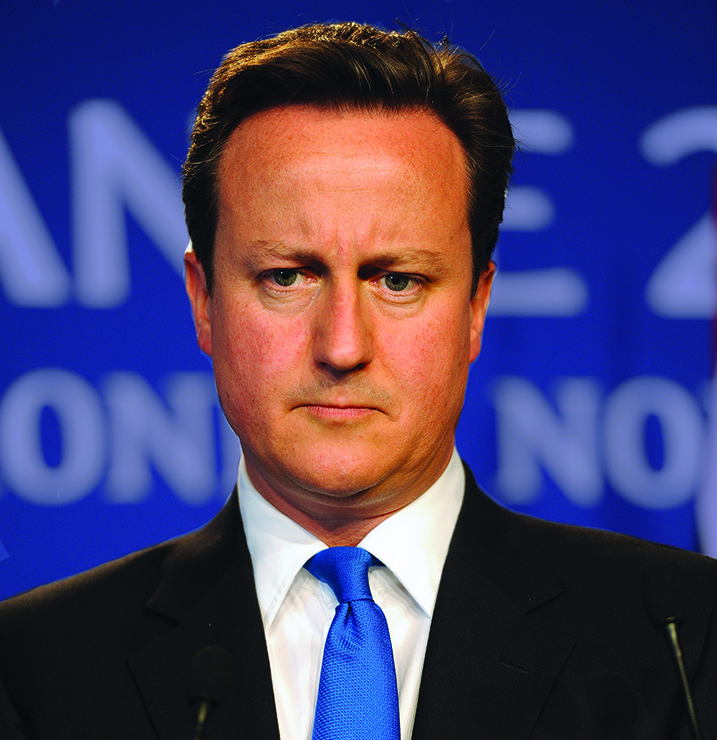

Who (except for the deliberately contrary host Piers Morgan) could disagree? Leavers and Remainers can agree it is a chaotic mess, and David Cameron, the man who kicked it all off, is nowhere to be seen.

The fact that Cameron is absent is probably a blessing in disguise, as he is possibly the only man in Britain capable of making an even bigger mess of Brexit. Brexit only happened because of an incredible series of cock-ups and errors on the part of Dave.

Mistake #1

Promising a referendum for party political reasons

David Cameron has always been a committed Europhile and a supporter of the UK’s membership of the European Union, so it would seem pointless calling a referendum introducing the possibility of giving up something he wholeheartedly believed in. But the Conservative Party was facing internal disaffection during the years of the coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. Party members were getting restless with the centrist, consensual politics - and the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) led by Nigel Farage was attracting disenchanted Tory loyalists.

The Europe question had plagued the Conservative party for decades. In 1993, the Conservative PM John Major famously called a trio of his Eurosceptics ministers ‘bastards’ (widely thought to be Michael Howard, Peter Lilley and Michael Portillo).

The Conservative leaders who followed Major were all Eurosceptics: William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard). None came even close to defeating Tony Blair in a General Election (Duncan Smith wasn’t even given the opportunity and was dumped as his own party was convinced he had no chance).

The Conservatives desperately needed young blood and an injection of dynamism. So when the charismatic Cameron (Europhile) faced David Davis (Eurosceptic) in the 2005 leadership contest, Cameron easily won the support of the party. The party craved an energetic candidate to take on the all-powerful Tony Blair. Cameron declared he would “give this country a modern, compassionate Conservatism that is right for our times and right for our country.” The Europe question was on the back-burner - but it hadn’t gone away.

Labour’s long run in power came to an end in 2010, when Gordon Brown lost Labour’s Parliamentary majority, and Cameron negotiated a coalition with Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats.

It was inevitable that the Conservative right wing would rail against such a liaison, but the dissenting voices did not make an immediate impact. It might have to be a watered-down Conservative Government, but most Tories were just grateful that the 13 years in the wilderness were finally over.

The main opposition came from outside the party, where Farage’s skill at self-promotion and the ability to present himself a ‘man of the people’ was starting to make inroads. He described Cameron as “a socialist” whose priorities were “gay marriage, foreign aid, and wind farms”. Cameron countered with the assertion that UKIP was full of “fruitcakes, loonies, and closet racists.”

As the coalition government settled in, the voices from the right became more strident. But did Cameron really need to appease them with a promise of a referendum? In the 2010 General Election, UKIP hadn’t won a single seat and received just 3.1% of the total votes. It was true that UKIP made big advances over the following years and won 27% of the popular vote (the highest of all parties) in the 2014 European Parliament election, but the turnout was paltry. As stunning a victory as it seemed, the turn-out of 35.6% suggested the voters were apathetic about the whole Euro election.

Europe generated argument and fury within the Conservative party, but the wider population was generally uninterested. Polls before the 2015 election showed that only 3% of those surveyed chose Europe as the most pressing issue.

No matter, two years before in January 2013, Cameron pledged to hold a referendum during the early part of the next parliament IF the Conservatives won the next general election in 2015. But did he believe this would happen? When Cameron made this pledge a Conservative victory was by no means a shoe-in. In fact, an outright majority seemed virtually out of reach. A YouGov poll for the Sun at the time showed voting intentions as CON 33%, LAB 42%, LDEM 10%, UKIP 7%.

On the recent BBC2 fly-on-the-wall documentary Inside Europe: Ten Years of Turmoil, The EU Council president Donald Tusk reveals that Cameron told him there would never be a referendum, as his coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, would never allow it. Did Cameron promise a referendum, assuming that such an occurrence would never actually happen? Pledging the referendum united the party, and it seems that may have been the sole motivation.

The best Cameron hoped for was another Tory-Lib coalition, with the probable result of a Clegg veto on the referendum. The polls confirmed such a conclusion. Labour stayed ahead in the polls until the day of the vote, when the poll-of-polls showed the parties neck-and-neck. The polls were wrong. To everyone’s surprise Cameron won hands down gaining an overall majority of 12 seats. The referendum was on.

Donald Tusk’s verdict is telling: “The real victim of David Cameron’s success is David Cameron.”

Or in Michael Portillo’s words, it was: “The greatest blunder ever made by a British prime minister”.

Mistake #2

Alienating his Euro allies

Having won the election, Cameron had to fulfil two promises. He pledged to go to the EU to renegotiate a new deal and then he would put it to the vote. The first task was an abject failure. He came back from Europe virtually empty-handed having wildly over-estimated the appetite in Europe to change the rules.

Cameron maybe looked at a historical episode to justify his optimism. Dr Andrew Glencross, Senior Lecturer in International Politics at the University of Stirling, wrote: “In 1975, Harold Wilson won the referendum on remaining in the European Economic Community (EEC) on the back of a successful, if largely cosmetic, renegotiation. Prior to what the then Labour government called “Britain’s New Deal in Europe” opinion polls indicated there was in fact a majority to leave the EEC. The winning message in 1975 emphasised the advantages Wilson had succeeded in obtaining.

“The auspicious feature of a renegotiation this time round is that polls showed a clear preference among voters to stay in a reformed EU. All Cameron seemingly had to do was talk tough with EU leaders and come out with a piece of paper to wave to a thankful electorate. However, neither the reality nor the symbolism of the Prime Minister’s eventual deal did him any favours.”

Glencross reported that Cameron’s agreement “codified the UK’s special status as never before, which from an EU perspective was quite an achievement.” But, “ultimately, Cameron blundered by promising so much and delivering little when it came to the UK’s position within the EU. The renegotiation played into the Leave camp’s hand by confirming the weakness of the government’s position over immigration within the EU.”

Why did Cameron fail to secure a referendum-winning deal? According to many commentators he placed far too much reliance on German pragmatism, where the needs of the German car exporters would hold sway.

The Spectator’s James Kirkup, asserted that this was a big mistake: “Angela Merkel is central to the superstitious beliefs of some Brexiteers about how Germany and the EU operates, a view that suggests German carmarkers run Germany’s European policy and that Merkel would, in the final analysis, do anything to strike a deal allowing them to sell cars to the UK freely.

“‘Post Brexit a UK-German deal would include free access for their cars and industrial goods, in exchange for a deal on everything else,’ David Davis wrote a couple of months before becoming Britain’s main Brexit negotiator.

“In October 2016, Merkel clearly and publicly explained why this magical thinking cut no ice with her: preserving the EU project matters more to her and Germany than accommodating the parochial interests of either the UK government or the Conservative Party.

“For Merkel, a pick-and-choose approach to Europe was never an option. Cake was never on her menu, either before or after our referendum.”

In any case, Merkel was in no mood to offer favours to Cameron.

Kirkup recalls, “This story starts in 2005, when David Cameron stood for the Tory leadership. As a moderate, he was keen to woo the Right, especially on Europe. So he promised to pull the Tory MEPs out of the European People’s Party grouping in the European Parliament. He made the promise despite knowing that Merkel was concerned about the prospect of an institutional split between the Conservatives and her Christian Democrats. She even said so publicly.

“In 2009, the Tories duly left the EPP, severing an alliance which – though they did not value it – mattered quite a lot to the most influential leader in Europe. For some in Europe, that decision was proof that Cameron was a man to put party management ahead of statecraft. And leaders with such a reputation do not, as a whole, do well in European negotiations, especially with Merkel. Not that Cameron was daunted. Throughout his time as PM, he consistently overestimated his ability to win and retain support from Merkel, only to discover that she was not as committed to his cause as he had hoped.”

Cameron believed Merkel would be his firm ally in a campaign to keep the UK in Europe, yet he alienated her and had no understanding of where her priorities lay. It was a diplomatic cock-up of the highest degree.

Mistake #3

Leading the Remain campaign

Having set up an unnecessary referendum and failed to secure a new deal, he made his final fatal mistake – he over-estimated his own popularity.

In all elections there are votes that can be won – and ones that are virtually impossible to secure. Those that had held long-term political positions against Europe were never going to be swayed. Cosmopolitan London was always going to look to Europe. The Scots would rather have more power in Brussels than London. Northern Ireland and Gibraltar feared closed borders.

What of the provinces; the smaller cities, the towns and the villages? Much of the Home Counties were evenly split, with counties such as Surrey just leaning to Remain with tiny margins. Leave edged Sussex with just 50.23% of the vote.

It was in the north, the midlands, the south west and Wales where Leave had the big majorities. And the areas with the biggest margins had one thing in common, much of the population felt they were in areas that had been left behind. These were the areas with less employment opportunities, more people living in relative poverty and had suffered more from cuts to benefits and services.

And who did people blame? David Cameron and George “We’re all in this together” Osborne – the architects of austerity. Thiemo Fetzer, Associate Professor in Economics at University of Warwick, believes that austerity was a major driver of leave votes, enough to win the referendum. He writes: “The austerity-induced withdrawal of the welfare state since 2010 is a key driver to understand how pressures to hold an EU referendum built up and why the Leave side won.

“The fiscal contraction brought about by the Conservative-led coalition government starting 2010 was sizeable: aggregate real government spending on welfare and social protection decreased by around 16% per capita. At district-level, spending per person fell by 23.4% in real terms between 2010 and 2015, with the sharpest cuts in the poorest areas… Support for UKIP started to grow in areas with significant exposure to specific benefit cuts.

“Support for UKIP only started picking up significantly in areas and among individuals directly affected by welfare reforms once these cuts came into effect.”

The human cost of welfare cuts cannot be under-estimated and when presented with a choice between Remain or Leave, it is easy to read this as Remain or Change. If you are struggling to make ends meet, why would you choose to stay the same?

The campaign was led by the Prime Minister, the Chancellor and Nick Clegg (the man who back-tracked on tuition fees). Why would a voter in Stoke or Sunderland fall behind three wealthy establishment figures from Westminster, who had done so little to invest in their home towns and taken so many of their vital services away?

In effect the leaders of the Remain campaign sabotaged their own campaign just by being there.

The irony, of course, is that by giving the Westminster elite a bloody nose, the people in the north have helped concentrate even more power in Westminster.

Had the campaign to Remain been led by someone who was respected in the Labour heartlands, the result would surely have been very different.

David Cameron says he has no regrets about calling the referendum. No-one believes him of course. We may find out what he really thinks when he releases his memoirs this autumn. Who buys it is another matter.